It's one of those jobs that everybody knows, but few of us really think much much about. Tailors get all the credit for the style of clothing and quite naturally the merchants made all of the money, but most of the hard work come from the weavers. I first remember hearing about the weavers of Europe as a child, but mostly related to being put out of work as a result of the industrial revolution, the death of the "cottage industry" (followed by the Luddites). Obviously these industrious workers had a long run before that time, so I figured it was time to explore the intricate world of the weaver (sorry, was just imagining that last bit read as an intro to a PBS special or something).

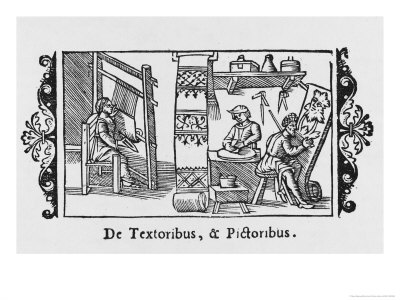

It's one of those jobs that everybody knows, but few of us really think much much about. Tailors get all the credit for the style of clothing and quite naturally the merchants made all of the money, but most of the hard work come from the weavers. I first remember hearing about the weavers of Europe as a child, but mostly related to being put out of work as a result of the industrial revolution, the death of the "cottage industry" (followed by the Luddites). Obviously these industrious workers had a long run before that time, so I figured it was time to explore the intricate world of the weaver (sorry, was just imagining that last bit read as an intro to a PBS special or something). Weaving was done at home in Medieval Europe. Weavers were often men, with the women of the house spinning the thread needed and helping with the finishing of the material. Cloths were primarily produced in wool, linen and nettlecloth (for the poor). Initially, the resultant products were sold at local faires. As the trades became more organized (forming guilds) in larger settlements, merchants became middle-men for the weavers. By the 13th Century, these merchants were both supplying the wool for the weaving as well as buying back the finished product, thereby dominating cloth production and controlling wages. Following the plague (1346), land prices dropped (increasing pasture land for sheep) and these new landlords moved weavers to those cottages (aka factories) in the countryside.

Weaving itself is simply the interlacing of warp (longitudinal lines) and weft (lateral lines). Warp threads are held taught, acting as the ground. A weft thread (a pick) is guided through the warp to make the pattern. Those patterns, oh god, a whole different post. The basic process of weaving on a loom is to first use the loom's heddles to make a space (a shed) for the pick to pass (shedding), then move the pick through the space (picking), and finally pushing the weft snugly up against the previous pick (beating-up or battening) using the reed (which looks like a comb). The pick may be shedded by hand or with a shuttle. Shuttles are normally pointed on both ends and the the filling yarn is mounted onto a quill, which is then mounted onto the shuttle. A selvage is formed at both edges of the fabric to prevent raveling (which surprisingly means unraveling), by looping the thread back into the weave. The selvage may or may not maintain the pattern of the rest of the cloth. Yes, this is the simplified version.

Weaving itself is simply the interlacing of warp (longitudinal lines) and weft (lateral lines). Warp threads are held taught, acting as the ground. A weft thread (a pick) is guided through the warp to make the pattern. Those patterns, oh god, a whole different post. The basic process of weaving on a loom is to first use the loom's heddles to make a space (a shed) for the pick to pass (shedding), then move the pick through the space (picking), and finally pushing the weft snugly up against the previous pick (beating-up or battening) using the reed (which looks like a comb). The pick may be shedded by hand or with a shuttle. Shuttles are normally pointed on both ends and the the filling yarn is mounted onto a quill, which is then mounted onto the shuttle. A selvage is formed at both edges of the fabric to prevent raveling (which surprisingly means unraveling), by looping the thread back into the weave. The selvage may or may not maintain the pattern of the rest of the cloth. Yes, this is the simplified version.  Loom styles have changed significantly through the course of history. With a Back Strap Loom (Southeast Asia and Americas still today), one end is tied to a fixed point and the other end loops around your back. Leaning back puts tension on the system, so you need to lean forward to create the shed. Because the weaver is tied to the machine, this limits the width of the cloth to arm's reach. The Warp-Weighted Loom is a vertical design which uses the aforementioned weights, suspended from a tree or beam, to keep tension on the warp. This may have been the earliest loom design, but it continued to see use in ancient Greece and spread throughout Europe. The Simple Frame Loom is effective, but generally only for smaller sized areas of cloth, as the weave is limited by the dimensions of the frame. The Horizontal Loom (11thC) was a big development, allowing continuous lengths of cloth to be produced by collecting the completed cloth in a roll in front of the weaver as new weft unrolls from the far end of the loom. Foot pedals were also used to lift the alternate sets of weft to create the shed. The Hand Loom (12thC) is a simple machine in which the heddles are all fixed, so that by raising the shaft, half of the warp lifts to create the shed. Similarly, lowering the shaft lowers the same half of the warp to create the shed (on the other side). Free-Standing Looms and Pit Looms are much larger endeavors. These looms both have multiple harnesses and foot-pedals (treadles) which allow a greater variety of patterns at a greater rate of speed. Other looms were developed between those discussed, some for specific types of products (narrow bands, tapestries, and so on), but these seem like a good overview for our present area (and level, sheesh) of interest.

Loom styles have changed significantly through the course of history. With a Back Strap Loom (Southeast Asia and Americas still today), one end is tied to a fixed point and the other end loops around your back. Leaning back puts tension on the system, so you need to lean forward to create the shed. Because the weaver is tied to the machine, this limits the width of the cloth to arm's reach. The Warp-Weighted Loom is a vertical design which uses the aforementioned weights, suspended from a tree or beam, to keep tension on the warp. This may have been the earliest loom design, but it continued to see use in ancient Greece and spread throughout Europe. The Simple Frame Loom is effective, but generally only for smaller sized areas of cloth, as the weave is limited by the dimensions of the frame. The Horizontal Loom (11thC) was a big development, allowing continuous lengths of cloth to be produced by collecting the completed cloth in a roll in front of the weaver as new weft unrolls from the far end of the loom. Foot pedals were also used to lift the alternate sets of weft to create the shed. The Hand Loom (12thC) is a simple machine in which the heddles are all fixed, so that by raising the shaft, half of the warp lifts to create the shed. Similarly, lowering the shaft lowers the same half of the warp to create the shed (on the other side). Free-Standing Looms and Pit Looms are much larger endeavors. These looms both have multiple harnesses and foot-pedals (treadles) which allow a greater variety of patterns at a greater rate of speed. Other looms were developed between those discussed, some for specific types of products (narrow bands, tapestries, and so on), but these seem like a good overview for our present area (and level, sheesh) of interest. The last area I want to touch on is spinning, which is the production of the yarn used in weaving (plus I always heard about it in fairy tales). The basic idea is to draw out the individual strands, twist them together for strength, and then wind them onto a spindle (or bobbin) for later use. Unfortunately, the spinning wheel wasn't available until the High Middle Ages, leaving us with the spindle and distaff to do the work (so much for the fairy tales). The distaff was basically a stick for holding the mass of material to be spun. This was placed under the arm or tucked in the girdle to leave the left hand free to draw out the strands. The spindle is also basically a stick with a split in the top to start the twist. It is held in the right hand and collects the twisted yarn. The twirling of the spindle gives the yarn its twist, before being wrapped onto the finished mass. Spinning was such a common (and useful) practice that many unmarried women did it in their free time, giving rise to the term spinster.

The last area I want to touch on is spinning, which is the production of the yarn used in weaving (plus I always heard about it in fairy tales). The basic idea is to draw out the individual strands, twist them together for strength, and then wind them onto a spindle (or bobbin) for later use. Unfortunately, the spinning wheel wasn't available until the High Middle Ages, leaving us with the spindle and distaff to do the work (so much for the fairy tales). The distaff was basically a stick for holding the mass of material to be spun. This was placed under the arm or tucked in the girdle to leave the left hand free to draw out the strands. The spindle is also basically a stick with a split in the top to start the twist. It is held in the right hand and collects the twisted yarn. The twirling of the spindle gives the yarn its twist, before being wrapped onto the finished mass. Spinning was such a common (and useful) practice that many unmarried women did it in their free time, giving rise to the term spinster. Goodness, I really had no idea what I was getting into when I started all of this. Even the simple mechanics of this require some fair three-dimensional thinking. It makes me boggle a bit to start thinking of changing colors and patterns in the weave. It's no wonder that guilds existed to share the skills and regulate the trade of the medieval weaver. However weaving was not done solely by the professional. Small communities might have a large frame loom for shared use. Many of the poor could not afford to buy their own cloth, but looms were also very expensive. They might instead take their spun wool to a nearby weaver, much like a farmer taking their grain to the mill. The weaving of cloth was obviously an important job in every community. I hope our little investigation today adds a member to a community you create some day.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Weaving#Medieval_Europe

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loom

http://www.history.uk.com/clothing/weaving-on-off-looms/

http://scholar.chem.nyu.edu/tekpages/loom.html

simple frame loom demo - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=61jdqH0Ji_4

http://www.cd3wd.com/cd3wd_40/vita/handloom/en/handloom.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hand_spinning

Bosnian woman hand spinning wool - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1R03D_QWVdc

In ancient Rome, bathing was one of the most common daily activities and easily within the budget of most free Roman men. In 354AD, 952 bathing facilities of various sizes were identified in Rome. Three thousand bathers could be accommodated in the Baths of Diocletian. These facilities were not for bathing alone, but included a wide variety of leisure time pursuits, including exercise, food, drink, music, and massage. The goal of the Roman bath was to induce sweating. The bather would start with a cold water dip and then go through a series of incrementally warmer rooms reaching around 100 degrees F (and 100% humidity). Dirt was removed from the skin by applying oil and scraping with metal tools. Early bathing facilities had separate sections for men and women, but mixed bathing was common by the First Century AD. The Romans carried their love of bathing throughout the Empire and exploited natural mineral baths wherever they found them.

In ancient Rome, bathing was one of the most common daily activities and easily within the budget of most free Roman men. In 354AD, 952 bathing facilities of various sizes were identified in Rome. Three thousand bathers could be accommodated in the Baths of Diocletian. These facilities were not for bathing alone, but included a wide variety of leisure time pursuits, including exercise, food, drink, music, and massage. The goal of the Roman bath was to induce sweating. The bather would start with a cold water dip and then go through a series of incrementally warmer rooms reaching around 100 degrees F (and 100% humidity). Dirt was removed from the skin by applying oil and scraping with metal tools. Early bathing facilities had separate sections for men and women, but mixed bathing was common by the First Century AD. The Romans carried their love of bathing throughout the Empire and exploited natural mineral baths wherever they found them.  Bathing in Japan is an important part of everyday life. However, baths are for relaxing, not for cleaning. It is important to clean yourself before entering the bath, because the bath water will be used by the entire family (when one is available in the home) or other members of the community. Parents may bathe with children and colleagues may bathe together at an onsen (geothermal) resort. Japanese tubs are generally deeper than western ones, allowing the user to soak up to the chin. The water is also much hotter than westerners are used to encountering. Public bath houses either had a deep pool for bathing or were primarily steam baths. Separating by gender began in the 17thC, but they went back and forth on this. Prostitution was apparently a bit of an issue with the yuna (hot water women), who later were relegated to the red light districts.

Bathing in Japan is an important part of everyday life. However, baths are for relaxing, not for cleaning. It is important to clean yourself before entering the bath, because the bath water will be used by the entire family (when one is available in the home) or other members of the community. Parents may bathe with children and colleagues may bathe together at an onsen (geothermal) resort. Japanese tubs are generally deeper than western ones, allowing the user to soak up to the chin. The water is also much hotter than westerners are used to encountering. Public bath houses either had a deep pool for bathing or were primarily steam baths. Separating by gender began in the 17thC, but they went back and forth on this. Prostitution was apparently a bit of an issue with the yuna (hot water women), who later were relegated to the red light districts.  Religion is a common reason for construction on a biblical scale (see?). The Great Pyramid of Giza was constructed over two million limestone blocks, weighing an average of 2.5 tons (yeah, more than 5 million tons of limestone, plus a measly 8,000 tons of casing granite) over the course of 10-20 years. The pyramid shape itself is thought to represent the rays of the sun. It was said that the Sun god (Ra) created himself from a pyramid shaped mound of earth before creating the other gods. The Pharaoh was both king and god to his people. Combine the divinity of the pharaoh with the symbolism inherent in the shape and we begin to see why these things took the shape they did (plus you had to make it tough to rob them). These structures both humbled and inspired the masses with the power of their god, especially in 2560 BC. Other examples of religious veneration would include massive statues of Buddha, the Statue of Zeus at Olympia, and possibly the entire city of Machu Picchu. Many religious buildings of today (churches, mosques, synagogs) follow the same formula.

Religion is a common reason for construction on a biblical scale (see?). The Great Pyramid of Giza was constructed over two million limestone blocks, weighing an average of 2.5 tons (yeah, more than 5 million tons of limestone, plus a measly 8,000 tons of casing granite) over the course of 10-20 years. The pyramid shape itself is thought to represent the rays of the sun. It was said that the Sun god (Ra) created himself from a pyramid shaped mound of earth before creating the other gods. The Pharaoh was both king and god to his people. Combine the divinity of the pharaoh with the symbolism inherent in the shape and we begin to see why these things took the shape they did (plus you had to make it tough to rob them). These structures both humbled and inspired the masses with the power of their god, especially in 2560 BC. Other examples of religious veneration would include massive statues of Buddha, the Statue of Zeus at Olympia, and possibly the entire city of Machu Picchu. Many religious buildings of today (churches, mosques, synagogs) follow the same formula.  Especially with the decline of religion, political reasons are some of the best ones for modern era monsters. The Washington Monument (completed 1884) was constructed as a symbol of unity for the USA, celebrating a universally loved political figure with materials from every state. The statue of Stalin (1955, pictured) perched on Letna Hill in Prague (demolished 1962), is a more modern example of replacing religious with political figures. The Soviets were great for building huge nationalistic monuments (I thought the one in the Tiergarten in Berlin was very impressive). Grand monuments of a political nature (including most legislative buildings I know of) function much as their religious counterparts. They are demonstrations of power and intended to display the portrayed in their idealized and super-human form. They are visual focal points to emphasize the power and majesty of the State.

Especially with the decline of religion, political reasons are some of the best ones for modern era monsters. The Washington Monument (completed 1884) was constructed as a symbol of unity for the USA, celebrating a universally loved political figure with materials from every state. The statue of Stalin (1955, pictured) perched on Letna Hill in Prague (demolished 1962), is a more modern example of replacing religious with political figures. The Soviets were great for building huge nationalistic monuments (I thought the one in the Tiergarten in Berlin was very impressive). Grand monuments of a political nature (including most legislative buildings I know of) function much as their religious counterparts. They are demonstrations of power and intended to display the portrayed in their idealized and super-human form. They are visual focal points to emphasize the power and majesty of the State. Self defense seems like a reasonable excuse to build gargantuan structures. Himeji Castle (depicted) is the largest of its kind in Japan, consisting

of 83 buildings and covering 576 acres (current form since 1618). The 1609

expansion is estimated to have taken over 25 million man-days. The

castle was designed not only to be beautiful (the white plaster was also

fireproofing) and functional (over 1000 loopholes for firing from) but

labyrinthine to confuse attackers on the way in. Massive castles of

this type functioned as a strong military defense and symbol of power

for the ruler, as well as being a psychological deterrent for his enemies. Commonly thought to be the only man-made structure visible from space, the Great Wall of China was constructed to protect against invasion from the north (the version we think of is 14thC or more recent). The Romans tried it too with Hadrian's Wall (begun around 122 AD). While it has been argued that it was intended more to regulate trade than keep out ravening bands of Scots, the construction of an 80 (Roman) mile wall certainly demonstrated the might of the Roman Empire to the locals.

Self defense seems like a reasonable excuse to build gargantuan structures. Himeji Castle (depicted) is the largest of its kind in Japan, consisting

of 83 buildings and covering 576 acres (current form since 1618). The 1609

expansion is estimated to have taken over 25 million man-days. The

castle was designed not only to be beautiful (the white plaster was also

fireproofing) and functional (over 1000 loopholes for firing from) but

labyrinthine to confuse attackers on the way in. Massive castles of

this type functioned as a strong military defense and symbol of power

for the ruler, as well as being a psychological deterrent for his enemies. Commonly thought to be the only man-made structure visible from space, the Great Wall of China was constructed to protect against invasion from the north (the version we think of is 14thC or more recent). The Romans tried it too with Hadrian's Wall (begun around 122 AD). While it has been argued that it was intended more to regulate trade than keep out ravening bands of Scots, the construction of an 80 (Roman) mile wall certainly demonstrated the might of the Roman Empire to the locals.  Alright, so after reading the title to this post, you might have asked yourself, "Why is Ben writing a post about smoking? Tobacco wasn't introduced to Europe until the 16th Century." I have to admit that my blog may come across as a little rigid at times regarding accuracy. I thoroughly enjoy doing research and learning how things work (or worked). However, the point of all this is simply to know the rules before I break them. Yes, I like working in a pseudo medieval European setting, but if I want my characters to be smokers, I will figure out a way to make it so. Limitations are great to make things feel real, but the rule of cool is paramount (this is not intended as advocacy for smoking), and it's my world damn it.

Alright, so after reading the title to this post, you might have asked yourself, "Why is Ben writing a post about smoking? Tobacco wasn't introduced to Europe until the 16th Century." I have to admit that my blog may come across as a little rigid at times regarding accuracy. I thoroughly enjoy doing research and learning how things work (or worked). However, the point of all this is simply to know the rules before I break them. Yes, I like working in a pseudo medieval European setting, but if I want my characters to be smokers, I will figure out a way to make it so. Limitations are great to make things feel real, but the rule of cool is paramount (this is not intended as advocacy for smoking), and it's my world damn it.  Once the tobacco is harvested, it needs to be cured to increase the "smoothness" of the smoke. Air cured tobacco is hung in a well ventilated are for 4-8 weeks. Fire cured tobaccos are hung over smouldering hardwood fires for a period between 3 days and 10 weeks. Flue cured tobaccos run a flue up through the smokehouse to add heat, but no smoke to the tobacco for about a week, slowly raising the temperature over the period. Sun cured tobacco is generally done in the Mediterranean and seems pretty obvious. Sorry, but if you want more info on how the tobacco is processed into various usable forms, you'll either have to wait for a later post

or do some of your own research (this is getting way too long).

Once the tobacco is harvested, it needs to be cured to increase the "smoothness" of the smoke. Air cured tobacco is hung in a well ventilated are for 4-8 weeks. Fire cured tobaccos are hung over smouldering hardwood fires for a period between 3 days and 10 weeks. Flue cured tobaccos run a flue up through the smokehouse to add heat, but no smoke to the tobacco for about a week, slowly raising the temperature over the period. Sun cured tobacco is generally done in the Mediterranean and seems pretty obvious. Sorry, but if you want more info on how the tobacco is processed into various usable forms, you'll either have to wait for a later post

or do some of your own research (this is getting way too long). Pipes are my favorite form of tobacco enjoyment (so they get their own long paragraph). The first known pipes were shaped like a tube or and hourglass, made of stone (like soapstone or catlinite) and dated to the Woodland period (500BC-500AD). During the Mississippian period (900-1600 AD), these pipes evolved into highly decorative pieces depicting animals or people. Native Americans who did not have access to soft stone would make clay pipes. The first pipes made in Europe were of clay (kaolin). Over 3000 clay pipe makers have been identified in England alone. Clay pipes were usually made in two-piece molds of wood or iron. Wooden (hard woods with tight grains were used) pipes evolved slowly and carving centers first emerged in Germany, Austria and Hungary. Porcelain pipes emerged in the late 18th C and were often hand painted with a variety of subject matter. Meerschaum pipes (began 18th C, in Turkey) are the white pipes still available today. While resembling clay, the material is mined and carved into the desired shape (preferred styles have changed dramatically over time). This material will change color as a result of smoking, turning amber, honey or even red in hue. Briar pipes (the most popular today) developed in the 19th Century. Briarwood comes from the burl of the heath tree, which grows in arid regions around the Mediterranean. Corn cob pipes are a cheaper option. The dried cobs are hollowed out to form the bowl and dipped in some kind of plaster mixture before finishing (make at home doesn't require the plaster, but cobs are dried for up to 2 years prior to use). Pipes came in all shapes and sizes (though most had small bowls because tobacco was expensive early on) with the level of decoration depending primarily on current trends and the affluence of the smoker.

Pipes are my favorite form of tobacco enjoyment (so they get their own long paragraph). The first known pipes were shaped like a tube or and hourglass, made of stone (like soapstone or catlinite) and dated to the Woodland period (500BC-500AD). During the Mississippian period (900-1600 AD), these pipes evolved into highly decorative pieces depicting animals or people. Native Americans who did not have access to soft stone would make clay pipes. The first pipes made in Europe were of clay (kaolin). Over 3000 clay pipe makers have been identified in England alone. Clay pipes were usually made in two-piece molds of wood or iron. Wooden (hard woods with tight grains were used) pipes evolved slowly and carving centers first emerged in Germany, Austria and Hungary. Porcelain pipes emerged in the late 18th C and were often hand painted with a variety of subject matter. Meerschaum pipes (began 18th C, in Turkey) are the white pipes still available today. While resembling clay, the material is mined and carved into the desired shape (preferred styles have changed dramatically over time). This material will change color as a result of smoking, turning amber, honey or even red in hue. Briar pipes (the most popular today) developed in the 19th Century. Briarwood comes from the burl of the heath tree, which grows in arid regions around the Mediterranean. Corn cob pipes are a cheaper option. The dried cobs are hollowed out to form the bowl and dipped in some kind of plaster mixture before finishing (make at home doesn't require the plaster, but cobs are dried for up to 2 years prior to use). Pipes came in all shapes and sizes (though most had small bowls because tobacco was expensive early on) with the level of decoration depending primarily on current trends and the affluence of the smoker.

Historic kitchens are fascinating places. I look around my (thoroughly) modern kitchen and am astounded by the sheer number of labor-saving devices that are at my disposal. Forget microwaves and garbage disposals. Think of the toaster and the coffeemaker. Granted, the Medieval cook wouldn't need a can opener, but you see a bit of what I'm driving at. The modern idea of "cooking from scratch" is nothing compared to what these people had to do every day. So the question is, "How do you create a 'Fantasy' kitchen?"

Historic kitchens are fascinating places. I look around my (thoroughly) modern kitchen and am astounded by the sheer number of labor-saving devices that are at my disposal. Forget microwaves and garbage disposals. Think of the toaster and the coffeemaker. Granted, the Medieval cook wouldn't need a can opener, but you see a bit of what I'm driving at. The modern idea of "cooking from scratch" is nothing compared to what these people had to do every day. So the question is, "How do you create a 'Fantasy' kitchen?" The needs of any kitchen are reliant on what you plan to cook in it. The poor of medieval Europe ate lots of brown bread, grains, onions and root vegetables, legumes, eggs, cheese and fish. They might have a skilled, a pot and a spit. Bread was often baked in clay pots in the embers of the fire. One of the most common dishes was potage (a stew of legumes/grains, onion, roots, greens, herbs and maybe some meat or a soup bone). The nobility might dine on roasted or boiled game, well spiced (not spicy) sauces, fowl, soup, pies and tarts, white bread, fritters and pancakes, fruits, vegetables, and so on. Their needs were a bit more extensive. It was interesting to discover that menus were developed to follow the medical concept of maintaining balanced humors (hot/dry/wet/cold, in this application). Consequently, beef (dry/cold) was often boiled, while pork (wet) was roasted. It was also common for food to be well ground and mixed to spread these properties evenly and ease digestion.

The needs of any kitchen are reliant on what you plan to cook in it. The poor of medieval Europe ate lots of brown bread, grains, onions and root vegetables, legumes, eggs, cheese and fish. They might have a skilled, a pot and a spit. Bread was often baked in clay pots in the embers of the fire. One of the most common dishes was potage (a stew of legumes/grains, onion, roots, greens, herbs and maybe some meat or a soup bone). The nobility might dine on roasted or boiled game, well spiced (not spicy) sauces, fowl, soup, pies and tarts, white bread, fritters and pancakes, fruits, vegetables, and so on. Their needs were a bit more extensive. It was interesting to discover that menus were developed to follow the medical concept of maintaining balanced humors (hot/dry/wet/cold, in this application). Consequently, beef (dry/cold) was often boiled, while pork (wet) was roasted. It was also common for food to be well ground and mixed to spread these properties evenly and ease digestion.  Still today, heat source is a very important concern for cooks. Naturally, in the medieval period the fuel choice was generally wood or peat. It seems, few cooks who lived in towns or cities would keep fires burning all night (unless, perhaps, it was winter). Fuel was much too expensive to waste in such a manner. Fires were generally lit with the assistance of a tinderbox (flint and steel). The application of heat (no thermometers, silly) was determined based on the color of the fire and controlled by the distance from the flame. Hearths often had multiple hooks at various heights for just that purpose. Similarly, spits would be placed at different heights, dependent on what you were roasting. Some castle hearths were big enough to roast three oxen simultaneously.

Still today, heat source is a very important concern for cooks. Naturally, in the medieval period the fuel choice was generally wood or peat. It seems, few cooks who lived in towns or cities would keep fires burning all night (unless, perhaps, it was winter). Fuel was much too expensive to waste in such a manner. Fires were generally lit with the assistance of a tinderbox (flint and steel). The application of heat (no thermometers, silly) was determined based on the color of the fire and controlled by the distance from the flame. Hearths often had multiple hooks at various heights for just that purpose. Similarly, spits would be placed at different heights, dependent on what you were roasting. Some castle hearths were big enough to roast three oxen simultaneously.  Furnishings in kitchens of this period were limited and often rough, even in the houses of the nobility. Open space is very important in working kitchens to allow freedom of

movement around other stations. Professional kitchens often had high ceilings because of the smoke and to reduce the risk of fire. Storage shelves were also high on the walls, as were windows. Rushes often covered the floor (which might have been hard packed earth, stone or tile) and were changed often (old ones helped to kindle the new fire). Trestle tables were common, due to ease of assembly/dis-assembly. Chopping blocks were a necessity for processing animals. Seats were generally simple three-legged stools. With all of those people

sharing a space it must have been chaotic at times.

Furnishings in kitchens of this period were limited and often rough, even in the houses of the nobility. Open space is very important in working kitchens to allow freedom of

movement around other stations. Professional kitchens often had high ceilings because of the smoke and to reduce the risk of fire. Storage shelves were also high on the walls, as were windows. Rushes often covered the floor (which might have been hard packed earth, stone or tile) and were changed often (old ones helped to kindle the new fire). Trestle tables were common, due to ease of assembly/dis-assembly. Chopping blocks were a necessity for processing animals. Seats were generally simple three-legged stools. With all of those people

sharing a space it must have been chaotic at times.  Copious storage space has long been a necessity for a good kitchen. Certain items were kept in large quantities and stored in ways that are

not common today. Sacks, casks, and barrels were all used for storage.

Meats could be salted, smoked or dried and were then hung to keep them away from

vermin. Fats would be rendered and stored in glazed earthenware

crocks. Fruits, nuts and vegetables might be preserved in honey. The

more expensive spices may be locked away like the silver. The buttery

(where they kept the butts of wine and ale; run by the butler) would

most certainly be locked, to keep the staff honest. A root cellar might be important to keep things cool, as well as out of the way. Where to keep things is often as important as how to cook them.

Copious storage space has long been a necessity for a good kitchen. Certain items were kept in large quantities and stored in ways that are

not common today. Sacks, casks, and barrels were all used for storage.

Meats could be salted, smoked or dried and were then hung to keep them away from

vermin. Fats would be rendered and stored in glazed earthenware

crocks. Fruits, nuts and vegetables might be preserved in honey. The

more expensive spices may be locked away like the silver. The buttery

(where they kept the butts of wine and ale; run by the butler) would

most certainly be locked, to keep the staff honest. A root cellar might be important to keep things cool, as well as out of the way. Where to keep things is often as important as how to cook them.

Sewers have been utilized by civilizations off and on since at least 2500BC in Eshnunna. Some had water flushed latrines (even London had a few tidally flushed by the Themes). Others had associated septic tanks for the collection of material outside of the city. Brick, stone and even clay pipes have been used to construct these ancient disposal systems. However, in many cities of Europe a "sewer" simply meant a lined ditch intended for storm water, which flowed into the nearest stream or river. Some communities connected these storm water drains to simple cesspools, which would then drain back into the water supply. The sludge would be contained (producing a lovely odor, naturally) and mucked out at need. The vaunted sewers of Paris (begun in 1370) at the outset only redirected waste water from the Seine to the "Ménilmontant" brook. Even in more recent history, natural waterways have been enclosed (my parents remember some old streams in Philadelphia that used to run interesting colors due to a nearby chemical plant) to serve as sewers and protect residents from direct contact with the waste.

Sewers have been utilized by civilizations off and on since at least 2500BC in Eshnunna. Some had water flushed latrines (even London had a few tidally flushed by the Themes). Others had associated septic tanks for the collection of material outside of the city. Brick, stone and even clay pipes have been used to construct these ancient disposal systems. However, in many cities of Europe a "sewer" simply meant a lined ditch intended for storm water, which flowed into the nearest stream or river. Some communities connected these storm water drains to simple cesspools, which would then drain back into the water supply. The sludge would be contained (producing a lovely odor, naturally) and mucked out at need. The vaunted sewers of Paris (begun in 1370) at the outset only redirected waste water from the Seine to the "Ménilmontant" brook. Even in more recent history, natural waterways have been enclosed (my parents remember some old streams in Philadelphia that used to run interesting colors due to a nearby chemical plant) to serve as sewers and protect residents from direct contact with the waste.  Shitting is one of those basic facts of life that is easily skipped over in most writing (though it can be used to great effect, see: Martin, George R R). It is however a necessity for all people and the remains must be dealt with for the sake of health and atmosphere. In a large percentage of situations, this involves the use of a privy. The privy (necessary, shitter, what have you) is generally a collection place, but in castles they were at times built on exterior walls, projecting over the moat. In cities, privies were often located in the cellar and might be as simple as a wooden board placed over an open hole. There are stories of these boards breaking and the unfortunate resting

upon them departing this life in a most distasteful manner. Alternatively, chamber pots might be used and emptied into the basement cesspit. Though it was usually outlawed, it was not uncommon for the contents of the chamberpot to be simply flung out the window (people were lazy at times back then too). Once these cesspits reached capacity, it was time to call the gong farmer. Yep, guys came to your place to shovel out your shit. This was usually regulated so it would only be done at night (since the cart rolling down the street afterwards can't have been pleasant). It was not terribly uncommon for these basement privies to become overfilled. Privies in rural areas, might be located in separate buildings from the main house (aka outhouses). These could either be harvested for fertilizer, or simply covered over and a new one dug at need.

Shitting is one of those basic facts of life that is easily skipped over in most writing (though it can be used to great effect, see: Martin, George R R). It is however a necessity for all people and the remains must be dealt with for the sake of health and atmosphere. In a large percentage of situations, this involves the use of a privy. The privy (necessary, shitter, what have you) is generally a collection place, but in castles they were at times built on exterior walls, projecting over the moat. In cities, privies were often located in the cellar and might be as simple as a wooden board placed over an open hole. There are stories of these boards breaking and the unfortunate resting

upon them departing this life in a most distasteful manner. Alternatively, chamber pots might be used and emptied into the basement cesspit. Though it was usually outlawed, it was not uncommon for the contents of the chamberpot to be simply flung out the window (people were lazy at times back then too). Once these cesspits reached capacity, it was time to call the gong farmer. Yep, guys came to your place to shovel out your shit. This was usually regulated so it would only be done at night (since the cart rolling down the street afterwards can't have been pleasant). It was not terribly uncommon for these basement privies to become overfilled. Privies in rural areas, might be located in separate buildings from the main house (aka outhouses). These could either be harvested for fertilizer, or simply covered over and a new one dug at need.  One of the simplest ways to dispose of trash is to burn it. Drive through rural communities today and you can still spot the odd trash fire. This serves multiple purposes. Heat is the obvious byproduct, which is great especially in winter months and in those places where it might not be easy or cheap to heat your home. Additionally, it is important to dispose of excess combustible material to protect against fires. When my parents were growing up in Philadelphia, they use to rake all of the leaves out in the street and burn them. Controlled burns are also used in forestry to limit the impact of wildfires. Burning trash is regulated in the US today primarily due to the presence of noxious chemicals that would be released into the air as a result of the combustion.

One of the simplest ways to dispose of trash is to burn it. Drive through rural communities today and you can still spot the odd trash fire. This serves multiple purposes. Heat is the obvious byproduct, which is great especially in winter months and in those places where it might not be easy or cheap to heat your home. Additionally, it is important to dispose of excess combustible material to protect against fires. When my parents were growing up in Philadelphia, they use to rake all of the leaves out in the street and burn them. Controlled burns are also used in forestry to limit the impact of wildfires. Burning trash is regulated in the US today primarily due to the presence of noxious chemicals that would be released into the air as a result of the combustion.  Water from mineral streams can also be evaporated in vessels. Otherwise, the salt must be mined.Salt deposits are known throughout the world (where seas and lakes have dried up). Mineral springs are of course natural in the area of such deposits and the medicinal value of "taking the waters" has been much debated. Salt mining was one of the most dangerous occupations available before industrialization, due to rapid dehydration and massive sodium intake (well, and cave-ins and assorted regular mine dangers). Consequently, it was often done by prison or slave labor (I remember my father saying, "Off to the salt mines," in jest on his way to work).

Water from mineral streams can also be evaporated in vessels. Otherwise, the salt must be mined.Salt deposits are known throughout the world (where seas and lakes have dried up). Mineral springs are of course natural in the area of such deposits and the medicinal value of "taking the waters" has been much debated. Salt mining was one of the most dangerous occupations available before industrialization, due to rapid dehydration and massive sodium intake (well, and cave-ins and assorted regular mine dangers). Consequently, it was often done by prison or slave labor (I remember my father saying, "Off to the salt mines," in jest on his way to work).