It has been some time since I broached this topic, leaving you on the edges of your seats. For that I do apologize. Okay okay, so maybe there are very few of you who read that first installment. I know that few of you have gone back into the history of this blog to see where it all began, instead preferring to wait for the new and exciting every week. Let me encourage you to do differently. Unlike other information sources, I try to avoid repeating myself (except when telling you to read more of my work and to leave comments and suggestions), so that topic you have hoped for may have already been covered! That being said, on with the show.

Any basic study of evolution will show you that plants and animals of different types arose on different land masses. When continental drift tore land masses apart, those species present on multiple continents evolved in different ways (or died out), as best fit their environment. It was not until humanity began exploring and carrying species to different land masses, that many of these species were introduced to other regions. By limiting which species are generally available to our creatures, writers significantly impact the culture of those creatures (yeah I had a little trouble figuring out where to file this article). The presence of large domesticated animals has significant impact on enabling modern (and Medieval European) life.

Farming is a cornerstone of modern society. Humans have been doing it for thousands of years. You dig a hole in the ground, put some seeds in, give it some water and *presto*, food. Ah, if only it were so simple. Anyway, hoeing your row is backbreaking work. With the aid of our large domesticated friends (horses, oxen, donkeys, etc) it became much easier to work a larger area of land. Their strength also made useful land of areas previously thought unworkable due to the presence of too many rocks or trees. Do not overlook the fact that these large animals also provide a great source of fertilizer (I seem to remember that using the human stuff is a bad idea). By enabling farmers to spread out and be more efficient, these labor saving machines increase food production, which allows for more free time. Free time from agriculture is what enables every other trade.

Big domesticated animals make a lovely food source. Domesticated cows/horses/oxen/etc provide a readily available source of meat that replenishes itself, which we don't have to go after with spears. Along with this, we get the joy of cheese, butter and other milk products. Just like farmers, hunters who don't need to go out so often (or at all) are more efficient and can take up other trades. An added bonus is that they are less likely to die in the act of hunting a wild animal.

Having large domesticated animals to provide over-land transportation is a significant advantage for most cultures. These animals are put to use to carry humans and to pull carts. This allows more goods to be carried faster for trade while requiring less humans to do the work. Without these animals, there would have been no Silk Road. Information can flow more freely over larger distances with an horse carrying a messenger. Limits on communication are the limits on an empire. Camels make it possible to cross deserts impenetrable to humans because they can carry us and the water that we need to survive. It is the camel that allowed nomads to travel the deserts as the did (do?). We have harnessed these beasts to extend our reach to other lands and other cultures. They provide the connective tissue through inhospitable lands.

Warfare was changed through the application of large animals. The presence of cavalry is a game changer. They can break lines of infantry with a charge and trample the enemy under their hooves. The Mongols dominated from the Steppes of Russia to the Chinese interior for a time with their mounted bowmen. Horsemen also make fantastic scouts. Hannibal famously used elephants in battle and while crossing the Alps into Italy. Large animals also enable the baggage train which can carry provisions and siege equipment for an army. Like so many other areas, these animals don't replace humans, they just enable us to do these jobs better.

Now you are nodding along and wondering what all of this has to do with anything. As I've said before, when creating a world, it is the limitations we place on our cultures that help to differentiate them. The Americas did not have horses or cows before Europeans introduced them (though the natives adapted to them rather well). Likewise, Australia had no large domesticated animals of its own. Africa too lacked some of the species intrinsic to Europe's cultural evolution. Naturally, most islands don't the space or resources necessary to support these populations. Cultures that lack the advantage of large animals must find other ways to succeed. They may maintain a hunter/gatherer lifestyle (ex: Australian Aboriginal cultures). They may stay close to the sea and rely on it for food and transport (ex: Hawaiian Islands). A highly structured social organization may be employed to increase the efficiency of workers (ex: Aztec and Mayan cultures). Large domesticated animals are not a prerequisite for culture, but they are force (labor/military) multipliers. By removing these creatures from an area of your imaginary world, your new culture may evolve in a wonderful new way.

Follow the twistings and turnings of my mind as research into this world fuels my creation of others. Give it a read and you just might learn something. If you have some good information to share, feel free to learn me something in return. It's an ongoing process.

Tuesday, April 29, 2014

Thursday, April 24, 2014

Jobs - Tax Collector

At this time of year, the tax-man seems like an appropriate topic. The idea of taxation is as old as organized government. Taxation is the expedient that enables our political leaders (soldiers too) to focus their attentions on things other than putting food on the table. While not exactly the most popular person in any town, the tax collector is an essential element, who facilitates that movement of money and material. At times, the tax collectors were hated because taxes were high, at other times it was because of how they went about collecting them. Even Jesus used them as examples of the lowest of the low. I'd feel bad for the bastards, but they seem to have brought much of this hatred upon themselves.

Over the years, taxes have taken many forms. Poll taxes were generally a flat tax per individual (though some progressive taxes were employed). Import/export taxes could be used as a means to protect local business, as a luxury tax, or to pass governmental costs on to outsiders. Sales taxes were simply the government taking a percentage of commerce in general. Property taxes were payed by landowners and peasants alike. There was even a church tax in some of Medieval Europe formalizing the tithe (10%). Taxes could target specific groups who were more elusive (nomads) or members of the minority (dependent upon location, but generally including the Jews). Hey man, it's expensive to run a government.

There are three general forms in contracts between government and tax collector: share, rent, and wage. In share contracts, the tax man is offered a percentage of the total value collected from a region. Rent contracts were of two basic types based on how the payment was determined. In one type, the collectors bid against each other in an auction to determine who would get the contract. The other form involved bargaining between the government and the rent contractors to determine the actual value of the rent in question. Wage contracts agree to pay the tax collector a set amount based upon the labor involved in the collection (not an hourly wage). Any of these forms could be utilized regardless of whether the tax collector is a government functionary or a private contractor and different forms could be employed for different kinds of taxes within the same region.

The most essential issue for private collectors is understanding how much a specific area is worth (over the length of the contract). Governments naturally accept the highest bid. These collectors are then required to pay the government the agreed upon amount (lump sum or installments). Then it is up to the collector to recoup his investment as well as his pay. You can understand why they might be tenacious in their attempts to collect these taxes. Public servants were in no way immune to this effect. More valuable territories would be more highly sought after and awarded to those who could work them best (or were more politically favored). It is the gap between predicted value and actual value that leads to corruption and abuse.

Collecting taxes is a business, much like any other. However, the people who are being collected from don't generally see it that way. Tax collectors are thought of as leeches the world over. In a less connected world, it was much easier for people to hide their income (or production), or even skip town entirely when the tax man was on the prowl. Even today, most of us take every opportunity to pay the government the minimum amount possible. Assessing the true value of a business is a tricky matter at the best of times, try to include the variability of farming production and you have a very high stress job. It must be difficult to be lenient with the people when the money comes out of your own pocket.

Corruption and violence are the standard byproducts of financial dealings throughout history. Providing oversight of the tax-man can be extremely difficult, especially in large territories. Therefore, many tax officials has a significant amount of autonomy in their dealings. They were responsible for determining the specific amount owed by each individual. Is it surprising that they might not report a certain amount of each assessment? If goods were accepted in place of money, who is to say what is an appropriate value for those goods? When the people continuously try to evade paying, what is the tax-man to do? In some cases, tax-collectors might employ violence on a man's family to get him to return to town, or as warning to others who would think to do likewise. Tax collectors were renowned for their dogged attempts to collect from all within their reach. All too often, stories arose of unsavory methods of doing so.

Tax collectors are generally the villains of any tale in which they feature. Even today we have a thorough distaste for the trade (until they catch someone trying to hide an enormous fortune). However, they do play an important role in maintaining a central government. Without them, we could not pay for defense or complete any public works projects. Unfortunately, this type of work attracts those who are most avaricious and cruel, because that is what it takes to make the office lucrative (and function efficiently). These men are always viewed warily and usually live on the fringes of society. While many tax collectors earned the right to be despised, many were undoubtedly doing a difficult job in the best way they knew how.

World History - http://www.taxworld.org/History/TaxHistory.htm

Early History Applied to Modern Issues - http://www.taxhistory.org/thp/readings.nsf/ArtWeb/A5321448C7E17FF185256F0A0059A4BA?OpenDocument

Contract Types - http://digitalcommons.uconn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1196&context=econ_wpapers

Mesopotamia - http://world-history.nmhblogs.org/2012/09/30/trade-and-taxes-of-mesopotamia/

World Taxation - http://www.worldtaxation.com/uncategorized/history-of-taxation.html

Biblical References - http://www.bible-history.com/sketches/ancient/tax-collector.html

Over the years, taxes have taken many forms. Poll taxes were generally a flat tax per individual (though some progressive taxes were employed). Import/export taxes could be used as a means to protect local business, as a luxury tax, or to pass governmental costs on to outsiders. Sales taxes were simply the government taking a percentage of commerce in general. Property taxes were payed by landowners and peasants alike. There was even a church tax in some of Medieval Europe formalizing the tithe (10%). Taxes could target specific groups who were more elusive (nomads) or members of the minority (dependent upon location, but generally including the Jews). Hey man, it's expensive to run a government.

There are three general forms in contracts between government and tax collector: share, rent, and wage. In share contracts, the tax man is offered a percentage of the total value collected from a region. Rent contracts were of two basic types based on how the payment was determined. In one type, the collectors bid against each other in an auction to determine who would get the contract. The other form involved bargaining between the government and the rent contractors to determine the actual value of the rent in question. Wage contracts agree to pay the tax collector a set amount based upon the labor involved in the collection (not an hourly wage). Any of these forms could be utilized regardless of whether the tax collector is a government functionary or a private contractor and different forms could be employed for different kinds of taxes within the same region.

The most essential issue for private collectors is understanding how much a specific area is worth (over the length of the contract). Governments naturally accept the highest bid. These collectors are then required to pay the government the agreed upon amount (lump sum or installments). Then it is up to the collector to recoup his investment as well as his pay. You can understand why they might be tenacious in their attempts to collect these taxes. Public servants were in no way immune to this effect. More valuable territories would be more highly sought after and awarded to those who could work them best (or were more politically favored). It is the gap between predicted value and actual value that leads to corruption and abuse.

Collecting taxes is a business, much like any other. However, the people who are being collected from don't generally see it that way. Tax collectors are thought of as leeches the world over. In a less connected world, it was much easier for people to hide their income (or production), or even skip town entirely when the tax man was on the prowl. Even today, most of us take every opportunity to pay the government the minimum amount possible. Assessing the true value of a business is a tricky matter at the best of times, try to include the variability of farming production and you have a very high stress job. It must be difficult to be lenient with the people when the money comes out of your own pocket.

Corruption and violence are the standard byproducts of financial dealings throughout history. Providing oversight of the tax-man can be extremely difficult, especially in large territories. Therefore, many tax officials has a significant amount of autonomy in their dealings. They were responsible for determining the specific amount owed by each individual. Is it surprising that they might not report a certain amount of each assessment? If goods were accepted in place of money, who is to say what is an appropriate value for those goods? When the people continuously try to evade paying, what is the tax-man to do? In some cases, tax-collectors might employ violence on a man's family to get him to return to town, or as warning to others who would think to do likewise. Tax collectors were renowned for their dogged attempts to collect from all within their reach. All too often, stories arose of unsavory methods of doing so.

Tax collectors are generally the villains of any tale in which they feature. Even today we have a thorough distaste for the trade (until they catch someone trying to hide an enormous fortune). However, they do play an important role in maintaining a central government. Without them, we could not pay for defense or complete any public works projects. Unfortunately, this type of work attracts those who are most avaricious and cruel, because that is what it takes to make the office lucrative (and function efficiently). These men are always viewed warily and usually live on the fringes of society. While many tax collectors earned the right to be despised, many were undoubtedly doing a difficult job in the best way they knew how.

World History - http://www.taxworld.org/History/TaxHistory.htm

Early History Applied to Modern Issues - http://www.taxhistory.org/thp/readings.nsf/ArtWeb/A5321448C7E17FF185256F0A0059A4BA?OpenDocument

Contract Types - http://digitalcommons.uconn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1196&context=econ_wpapers

Mesopotamia - http://world-history.nmhblogs.org/2012/09/30/trade-and-taxes-of-mesopotamia/

World Taxation - http://www.worldtaxation.com/uncategorized/history-of-taxation.html

Biblical References - http://www.bible-history.com/sketches/ancient/tax-collector.html

Tuesday, April 22, 2014

Torches

So you built yourself a castle, a nice big dark castle. You’ve got a stout gate, arrow loops to

defend approaches, and high walls to dissuade attackers. The next question is, how are you going to

navigate this edifice without stubbing your toe?

Fireplaces are a good idea, but you can’t have those everywhere. I already covered candles in my post, “Jobs –

Chandler,” so that leaves us with oil lamps and torches. I know, I know, it’s an unwieldy topic that

should be split into two. Fine, I’ll

listen to my audience this one time and stick to that movie castle mainstay, the

torch.

First point to get out of the way is that torches were not used regularly indoors. Dependent upon materials used, torches are thought to have burned for an hour or less. Having servants changing out the castle's sconces every hour seems like a terrible waste of time. Without a flue to clear it out, smoke would have built up rather rapidly in any enclosed area and smudged the hell out of walls and ceilings. Lastly, large untended flames dangling over wooden floors (possibly covered in rushes) spitting sparks seems like a terrible idea. Torches would not be the medium of choice for providing regular illumination inside a building.

Now that we have dispensed with the castle illuminating idea, why the hell would I want to use a torch?

It's a good way to draw attention to yourself if you're lost in the wilds (otherwise, it's probably easier to see by star/moonlight). When you are in a cave, it might be a good idea to have some kind of illumination (though you may be overcome with smoke). Dramatic torchlit processions have long been popular for religious and political occasions of all kinds. Setting fire to something is often easier for soldiers or bandits if they have a torch handy. Torches are also popular with jugglers and other kinds of traveling entertainers. There are myriad occasions where torches can be useful, but you need to keep their limitations in mind.

While torches are widely depicted in art of the period, I haven't found much in the way of clearly referenced historical material related to their construction. It seems widely agreed that a wooden stave (preferably green or wet) was used for the handle. One end of the stave was then wrapped in a material and soaked with a flammable substance. The important idea was to keep the flammable material burning slowly. Most bark, reeds, or rags on their own would burn out in mere minutes. Pieces of highly resinous larch or pine were impregnated with wax for use as torches by early Celtic miners (900-400BC). In Italy, saplings were beaten into fibers at one end and treated with fat to make torches. Dictionary.com describes torch wood as "any of various resinous woods suitable for making torches, as the wood of the tree Amyris balsamifera, of the rue family, native to Florida and the West Indies." A. Roger Ekirch's At Day's Close, Night in Times Past (2005), says torches were "Made from thick, half-twisted wicks of hemp, dipped in pitch, resin, or tallow, a single torch weighed up to three pounds" (p. 124). It is clear that there are almost as many right ways to make a torch as there are wrong ways.

It's good to see that I haven't made any mistakes yet in regards to this in my writing, but it seems I have new nits to pick with loads of movies. Will I ever be able to watch "The Adventures of Robin Hood" the same way again? (You put movie titles in quotes, right?) It just goes to show how much of our understanding of the world is warped by the entertainment of our childhood (and adulthood). I'm using way too many parenthetical comments (aren't I?). Ah well, I suppose my characters will just have to go back to trimming their wicks (for their candles, come on people).

Pitfalls - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HQZqbGME5HY&hd=1

Forum with History and Construction - http://newsgroups.derkeiler.com/Archive/Soc/soc.history.medieval/2006-06/msg00554.html

Reddit Related Topic - http://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/1e7adh/weve_all_seen_the_unrealistic_torches_used_in/

Limited Resource- http://www.medievaltravel.co.uk/technology/medieval-technology-torches.html

Wiki - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Torch

An Author's Take - http://jillwilliamson.wordpress.com/2010/01/21/medieval-facts-lighting-part-two-torches/

First point to get out of the way is that torches were not used regularly indoors. Dependent upon materials used, torches are thought to have burned for an hour or less. Having servants changing out the castle's sconces every hour seems like a terrible waste of time. Without a flue to clear it out, smoke would have built up rather rapidly in any enclosed area and smudged the hell out of walls and ceilings. Lastly, large untended flames dangling over wooden floors (possibly covered in rushes) spitting sparks seems like a terrible idea. Torches would not be the medium of choice for providing regular illumination inside a building.

Now that we have dispensed with the castle illuminating idea, why the hell would I want to use a torch?

It's a good way to draw attention to yourself if you're lost in the wilds (otherwise, it's probably easier to see by star/moonlight). When you are in a cave, it might be a good idea to have some kind of illumination (though you may be overcome with smoke). Dramatic torchlit processions have long been popular for religious and political occasions of all kinds. Setting fire to something is often easier for soldiers or bandits if they have a torch handy. Torches are also popular with jugglers and other kinds of traveling entertainers. There are myriad occasions where torches can be useful, but you need to keep their limitations in mind.

While torches are widely depicted in art of the period, I haven't found much in the way of clearly referenced historical material related to their construction. It seems widely agreed that a wooden stave (preferably green or wet) was used for the handle. One end of the stave was then wrapped in a material and soaked with a flammable substance. The important idea was to keep the flammable material burning slowly. Most bark, reeds, or rags on their own would burn out in mere minutes. Pieces of highly resinous larch or pine were impregnated with wax for use as torches by early Celtic miners (900-400BC). In Italy, saplings were beaten into fibers at one end and treated with fat to make torches. Dictionary.com describes torch wood as "any of various resinous woods suitable for making torches, as the wood of the tree Amyris balsamifera, of the rue family, native to Florida and the West Indies." A. Roger Ekirch's At Day's Close, Night in Times Past (2005), says torches were "Made from thick, half-twisted wicks of hemp, dipped in pitch, resin, or tallow, a single torch weighed up to three pounds" (p. 124). It is clear that there are almost as many right ways to make a torch as there are wrong ways.

It's good to see that I haven't made any mistakes yet in regards to this in my writing, but it seems I have new nits to pick with loads of movies. Will I ever be able to watch "The Adventures of Robin Hood" the same way again? (You put movie titles in quotes, right?) It just goes to show how much of our understanding of the world is warped by the entertainment of our childhood (and adulthood). I'm using way too many parenthetical comments (aren't I?). Ah well, I suppose my characters will just have to go back to trimming their wicks (for their candles, come on people).

Pitfalls - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HQZqbGME5HY&hd=1

Forum with History and Construction - http://newsgroups.derkeiler.com/Archive/Soc/soc.history.medieval/2006-06/msg00554.html

Reddit Related Topic - http://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/1e7adh/weve_all_seen_the_unrealistic_torches_used_in/

Limited Resource- http://www.medievaltravel.co.uk/technology/medieval-technology-torches.html

Wiki - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Torch

An Author's Take - http://jillwilliamson.wordpress.com/2010/01/21/medieval-facts-lighting-part-two-torches/

Thursday, April 17, 2014

Forests and Succession

|

| N.R.Fuller, www.SayoStudio.com |

In a previous post, "The Nature You Know," I touched on an idea that I think is important to keep in mind while writing. So many of the images that we have of the natural world have been shaped by the way humans impact their surroundings that many of us have difficulty envisioning a truly natural environment. Even those of us who spend our leisure time walking in the woods, climbing mountains, or fly fishing usually experience nature as guided by human hands. While using these images in your story may be perfectly appropriate in many instances, it can be useful to know what our characters would actually encounter when they head out into the wilds. Most of our parks are not the pristine habitat we imagine them to be.

Succession is the idea that an area of cleared forest land (because of fire, high winds, etc.) will regrow in a predictable pattern. During this process not only the plants, but the animals who inhabit the area will change. These changes are brought about due to the changes in the availability of sunlight, nutrients, and water. The specific species taking part in this process will differ depending upon local climatic conditions (temperature, elevation, latitude). Early stage plant species are grasses and shrubs which thrive in bright sunlight. Following this, trees begin to sprout and competition really kicks into gear as species fight each other for resources. Eventually (presuming no catastrophic events) a mature forest will develop. At this stage, the leaf litter of the forest floor has decreased because the canopy has solidified, killing off the spreading lower branches you see on those solitary trees in farmers' fields. When a new area of the forest is cleared (due to fire, winds, insects, disease, etc.) the process begins anew.

Not all open ground will complete the cycle of succession. Plant populations are limited by the quantity and quality of the soil that is beneath them. While this seems like a simplistic statement, you'll want to keep it in mind. There is a significant reason why the NJ Pine Barrens don't have farms, and it isn't because we didn't try. The sandy acidic soil of this region is not so friendly. Similarly, grasslands remain grasslands mostly because of the poor quality (I'm not judging them, I promise) of the soil beneath them. While thin soils may change radically from one inch to another (due to a change in underlying rock type), the thicker soils underlying mature forests are less likely to have radical divisions. Consequently, many unaltered forests play out the gradations of succession on their fringes as the soil decreases in quality.

So, how do humans impact forests?

1) We fight fires. While controlled burns of public lands have long been advocated for as a more natural and cost effective way to manage our forests, we keep dumping chemicals on these massive tinderboxes to delay the inevitable. Consequently, forest fires tend to be more destructive, though less frequent. Natural forests would generally have more clearings (undergoing succession) and less accumulated litter (leaf and branch). Additionally, some species thrive specifically in the aftermath of fires.

2) Humans clear forests to provide farmland and to build roads. This creates that weird effect of having a stand of really tall straight trees next to open ground. Fresh cut stands are really obvious because there are no branches on the exposed sides of those trees, or they have those sad little branches sticking out from the otherwise barren trunk. Unless there is a significant change in the soil quality/thickness at that line, this is the result of a catastrophic event (human interaction included). Oh, this also includes clear-cutting to put up power lines and the like.

3) Logging has an impact on the forest for a variety of reasons. Obviously, the largest trees tend to be targeted, which impacts the animals that live in and around them (remember the spotted owl fiasco?). Modern techniques also tend to clear an area, instead of taking only the most desirable trees (which was more economically viable when being done by hand). Some forms will take only the trunk of the tree, leaving behind all of the scraps, making great tinder. Cable logging leaves long scars in the earth where logs were dragged en route to the trucks waiting below.

4) Paths that we cut through Parkland give a false sense of reality. These pathways are often leveled, widened, and cleared to make a more pleasant experience for the hikers. Secondly, pathways are often curved into switchbacks to decrease erosion. I'm going a little off topic here, but I'm pretty sure our predecessors didn't bother with this. Paths would most likely follow the shortest route, leading to rocky washed out trails in dry times, or swampy morasses in the rainy season.

5) Rerouting and damming rivers has a pretty obvious impact on forests. Most trees don't sprout when they're submerged in water (some coastal species like mangroves do weird things), so those barren trunks sticking up in the middle of the pond might not have gotten there naturally (though there are ways to do it). Take a look next time you see one and check if there is a dam or a road blocking the natural drainage.

I hope you enjoyed this little peek at the world around you. As always, let me know if you have something to add, or you think I screwed something up. Check out the links below for more detailed info on what I covered.

http://forest.wisc.edu/sites/default/files/pdfs/publications/78.PDF

http://www.envirothonpa.org/documents/ForestSuccession.pdf

http://www.georgian.edu/pinebarrens/

http://www.privatelandownernetwork.org/pdfs/benefits_of_prescribed_burning_low-res.pdf

http://www.bigskyfishing.com/National_parks/glacier/logging-lake-galleries/near-burn-area.php

http://www.ecofootage.com/vs0259.html

http://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/storms-reveal-7-500-year-old-drowned-forest-on-north-galway-coastline-1.1715303

Tuesday, April 15, 2014

Bookbinding

We all know that Gutenberg invented moveable type for his printing press in the 15th Century, but people had been putting books together long before they could mass produce them. Different cultures tackled the problem in various fascinating ways, dependent on what materials they had on hand, starting in the 1st Century BC. To keep this post a little focused, I'm going to focus on the European tradition.

European books are thought to have originated in Greece. Scrolls were felt to be too unwieldy (even the cool double rolled type) for referencing various parts of the text. To address this issue, scrolls began to be folded accordion style. Eventually (200AD?), pages were folded into quires (in half), stitched together, and bound into a codex, making the first book.

Ground materials for writing have taken many shapes. Wood, ivory and bronze have all been used. The Romans recorded business accounts on tablets that had been dipped in wax. Papyrus was employed by the Egyptians, but it was not a good material for folding and proved susceptible to moisture, degrading within 100 years in non-arid climates. A plentiful resource, most records were kept on papyrus until the 4th Century AD, when it was overtaken by parchment. Parchment is made from any animal skin (vellum being specifically from cows) and if maintained properly can last for 1,000 years. Paper made from linen rags began to be available in Europe around the 10th Century, becoming commonly used for small cheap texts around 1400AD. Parchment was more durable and provided a better material to write on, but paper was less expensive. With the advent of printing and the eventual increase in paper quality, paper came to dominate the market.

If you've ever folded paper, you know that after a certain number of sheets, the thickness begins to build up, pushing the outer sheet further and further out of line. To prevent this, multiple quires (or gatherings) are used to form larger books, each with a signature to mark its position in the book (before page numbers). A screw press or a beating stone and hammer were used to flatten the pages and allow them to lie closer together. After being pressed, the pages are then evened up with a very sharp knife. These flattened quires were then sewn together to produce the form we know today.

Bindings have evolved significantly over the years. Early books had simple soft covers, with the quires sewn directly into the cover. In the Middle Ages, the quires were generally sewn onto bands which sat at right angles to the spine, with techniques varying from place to place. Once sewn together, these pages were usually attached to quarter-inch thick wooden boards (wood varied by region). Boards were originally of the same dimensions as the pages, but later grew larger to protect the pages (ca 1200). The bands (holding the pages) were usually attached to the boards with wooden pegs. At this point, the book could be complete, or the wooden boards could be further covered with leather (other materials may have been common, but have not survived as well). Clasps might be used to hold the book closed (vellum could absorb humidity) and bosses were employed to protect the corners and surface. Over time, the boards decreased in thickness and started to be attached to each other and finally to the parchment. Even after paper came to take over the market, end pages were often made of parchment to protect the contents.

Well, that was fun. Maybe it helped spark your imagination as well. I'm a little disturbed by how much information I had to cut to make this post somewhat intelligible. I didn't venture into the business side, or even the first thing about the artists who did the writing and illumination (another post, woo-hoo). This was a journey, exploring how much I don't know about a topic. Unsurprisingly, that volume of material is enormous. If you liked the above, feel free to read more of my stuff and check out the sites listed below. I am far from an expert on this one. As always, if you have something to add, or you feel I screwed something up, let me know. I'm always happy to hear form you.

|

| http://www.sydneybookbinding.com/bookbinding-classes/coptic-book/ |

Medieval Bookbinding (very accessible) http://web.ceu.hu/medstud/manual/MMM/bookbinding.html

History and How-To - http://www.antithetical.org/restlesswind/plinth/bookbind2.html

Power Point on Binding - http://staff.lib.msu.edu/alstrom/presentations/bindinghistory.html

Medieval European Bindings (dense) - http://futureofthebook.com/medieval-bookbinding/

General History of European Books - http://www.leatherboundtreasure.com/history_of_books.html

Highly Detailed (14th C on) - http://www.aboutbookbinding.com/Books/Book-Binding-5.html

World Bookbinding History - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bookbinding

Thursday, April 10, 2014

Diet and Digestion

One of the ideas I've expressed in my Creature Culture posts is that I want all the denizens of my world to live in a reasonably realistic way. Moreover, I don't want all of these creatures to live the same way. It seems highly unlikely that all of my sentient species could evolve while all occupying the same environmental niche. One of the ways to vary this is by varying the diet of these creatures. The three basic kinds of animal diet are: carnivore, herbivore, and omnivore. How these physical systems have evolved to make different body plans work is an essential element of the beautiful variation in our world.

Carnivores

This category includes: cats, seals, eagles, snakes, salmon, etc. Creatures who eat almost solely animals are called obligate carnivores (including carnivorous plants). Carnivores can either be predators who hunt or ambush their meals, or they can be scavengers. These animals may also specialize, eating one specific type of prey (fish, insects, birds).

Digestive systems tend to be short in these animals, making them less able (or unable) to break down tough plant fibers. They are monogastric (the stomach has one chamber), beginning digestion as soon as the food enters the mouth..

These animals tend to have pointed teeth to aid in tearing apart prey. Consequently, even if they had the digestive capacity, they may not be equipped to chew or even grip the plants (have you watched a cat eating grass?).

Because carnivores are either hunters or opportunistic feeders, they may gorge themselves at each meal (African lions ingesting up to 90lbs in one meal), in case the next one is hard to find. It's estimated that a mountain lion kills a deer (preferred prey) every 9-14 days.

Herbivores

Herbivores typically have flat teeth, and mouths designed to grind and rasp. Contained within this category are not just cows and goats (which are ruminants), but many types of insects and birds, koalas, beavers, monkeys and so on. It is theorized that the larger the herbivore, the less it needs to consume each day, relative to its size. Beef cows will eat from 1.8-2.0% of their weight per day. A 26lb year-old beaver may eat 1.5lbs of aspen per day to maintain itself (5.7% of its body weight), or 3.6lbs for maximal growth (14%).

Ruminants in particular are fun for a couple of reasons. Their teeth continuously grow, making the constant wear caused by chewing tough plants a non-issue. The second adaptation is the four-chambered stomach which allows them to break down plant fibers. The first two chambers use fermentation to start breaking down the plant fibers. Solids are consolidated and spit back up to be broken down further mechanically (chewing the cud) before re-swallowing and eventual absorption into the system.

Omnivores

The category is defined by those animals who eat from a wide variety of sources (plant, animal, insect, fungus, algae, whatever). This term is a difficult one, since many "carnivores" include some plants as a percentage of their diets. Additionally, herbivores can digest meat, they just don't usually eat it in the wild (like how my brother used to feed his pet iguana dog food for protein). Many species have preferences one way or another, but will switch as opportunity or extreme permits/requires. Some species also eat different types of material at different life stages, making it all more complex (did you think nature was simple?).

Certain omnivores (like humans) show their adaptation in their dentistry, having teeth suitable for both tearing and grinding. Otherwise, there are few distinguishing characteristics for this category (which was, like many other terms, invented to help us put things into neat boxes). Omnivores tend to be most notable for their lack of specialization. This jack-of-all-trades nature allows omnivores to better adapt on the fly to the situation at hand.

There are so many different ways that animals have found to sustain themselves, it seems a shame to make all sentient Fantasy creatures act essentially human. I'm no vegetarian, but why aren't there some intelligent grazers out there? I've read a fair number of SciFi carnivores, but relatively few in Fantasy realms who still go out hunting regularly (except for all the damn wolf companions). Sure, the intelligent ones will learn to supplement their diets with the other end of the culinary spectrum, but it's time for putting a little more effort behind our creature creation. It really doesn't take that much work and it can yield some really fun nuggets for character development.

ps: Be careful when reading biology articles that mention evolution. They often seem to get their developmental ideas the wrong way around. Just me being picky.

http://beef.unl.edu/cattleproduction/forageconsumed-day

https://kb.osu.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/1811/5317/V67N04_242.pdf;jsessionid=AF7CC778DC47C943FDE9DBE3D885C5EF?sequence=1

http://www.aws.vcn.com/mountain_lion_fact_sheet.html

http://www.audubonmagazine.org/articles/climate/arctic-omnivore-s-dilemma-0

http://www.examiner.com/article/what-exactly-is-an-obligate-carnivore

http://animals.io9.com/how-do-red-and-giant-pandas-coexist-the-secret-is-in-t-1561988329/+rtgonzalez

Carnivores

This category includes: cats, seals, eagles, snakes, salmon, etc. Creatures who eat almost solely animals are called obligate carnivores (including carnivorous plants). Carnivores can either be predators who hunt or ambush their meals, or they can be scavengers. These animals may also specialize, eating one specific type of prey (fish, insects, birds).

Digestive systems tend to be short in these animals, making them less able (or unable) to break down tough plant fibers. They are monogastric (the stomach has one chamber), beginning digestion as soon as the food enters the mouth..

These animals tend to have pointed teeth to aid in tearing apart prey. Consequently, even if they had the digestive capacity, they may not be equipped to chew or even grip the plants (have you watched a cat eating grass?).

Because carnivores are either hunters or opportunistic feeders, they may gorge themselves at each meal (African lions ingesting up to 90lbs in one meal), in case the next one is hard to find. It's estimated that a mountain lion kills a deer (preferred prey) every 9-14 days.

Herbivores

Herbivores typically have flat teeth, and mouths designed to grind and rasp. Contained within this category are not just cows and goats (which are ruminants), but many types of insects and birds, koalas, beavers, monkeys and so on. It is theorized that the larger the herbivore, the less it needs to consume each day, relative to its size. Beef cows will eat from 1.8-2.0% of their weight per day. A 26lb year-old beaver may eat 1.5lbs of aspen per day to maintain itself (5.7% of its body weight), or 3.6lbs for maximal growth (14%).

Ruminants in particular are fun for a couple of reasons. Their teeth continuously grow, making the constant wear caused by chewing tough plants a non-issue. The second adaptation is the four-chambered stomach which allows them to break down plant fibers. The first two chambers use fermentation to start breaking down the plant fibers. Solids are consolidated and spit back up to be broken down further mechanically (chewing the cud) before re-swallowing and eventual absorption into the system.

Omnivores

The category is defined by those animals who eat from a wide variety of sources (plant, animal, insect, fungus, algae, whatever). This term is a difficult one, since many "carnivores" include some plants as a percentage of their diets. Additionally, herbivores can digest meat, they just don't usually eat it in the wild (like how my brother used to feed his pet iguana dog food for protein). Many species have preferences one way or another, but will switch as opportunity or extreme permits/requires. Some species also eat different types of material at different life stages, making it all more complex (did you think nature was simple?).

Certain omnivores (like humans) show their adaptation in their dentistry, having teeth suitable for both tearing and grinding. Otherwise, there are few distinguishing characteristics for this category (which was, like many other terms, invented to help us put things into neat boxes). Omnivores tend to be most notable for their lack of specialization. This jack-of-all-trades nature allows omnivores to better adapt on the fly to the situation at hand.

There are so many different ways that animals have found to sustain themselves, it seems a shame to make all sentient Fantasy creatures act essentially human. I'm no vegetarian, but why aren't there some intelligent grazers out there? I've read a fair number of SciFi carnivores, but relatively few in Fantasy realms who still go out hunting regularly (except for all the damn wolf companions). Sure, the intelligent ones will learn to supplement their diets with the other end of the culinary spectrum, but it's time for putting a little more effort behind our creature creation. It really doesn't take that much work and it can yield some really fun nuggets for character development.

ps: Be careful when reading biology articles that mention evolution. They often seem to get their developmental ideas the wrong way around. Just me being picky.

http://beef.unl.edu/cattleproduction/forageconsumed-day

https://kb.osu.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/1811/5317/V67N04_242.pdf;jsessionid=AF7CC778DC47C943FDE9DBE3D885C5EF?sequence=1

http://www.aws.vcn.com/mountain_lion_fact_sheet.html

http://www.audubonmagazine.org/articles/climate/arctic-omnivore-s-dilemma-0

http://www.examiner.com/article/what-exactly-is-an-obligate-carnivore

http://animals.io9.com/how-do-red-and-giant-pandas-coexist-the-secret-is-in-t-1561988329/+rtgonzalez

Tuesday, April 8, 2014

getting ink

When I was a child, my parents told me that only bikers and sailors had tattoos. While that is obviously no longer the case (if it ever was), I grew up thinking that tattoos were introduced to Europe in the 18th Century by sailors returning from voyages to the South Seas. While they may have revived this old custom in Europe, there is a long and varied history for this artistic medium that shows up on all continents and was only repressed in Europe by the rise of Christianity. I guess I should have known better, since they are outlawed in the Old Testament, but I somehow never put it all together. What follows is a cursory examination of the history of the medium.

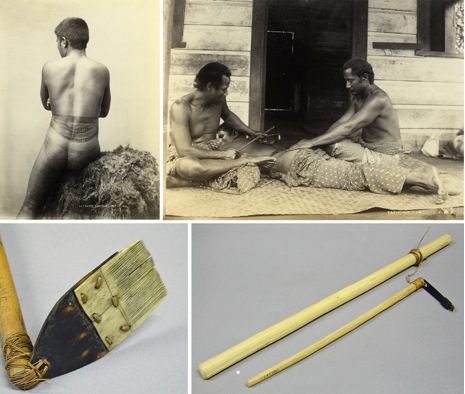

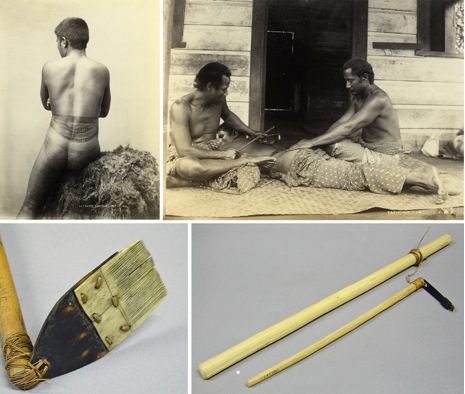

Polynesian tattooing goes back over two thousand years. The artists would use a variety of bone combs and a mallet to imprint the design. The ink was made from the soot of burnt lama nuts. Styles varied from island to island, but all are believed to have significant cultural meaning. Some designs spoke of rank, while others described the attributes of the bearer, with the juxtaposition of symbols giving shades of meaning conceived by the artist. The art itself was usually passed down from a master to a single apprentice (often father to son) because of its spiritual nature. Tattooing was a very painful process with a fair risk of infection lasting ten days (for men), but to halt the process would lead to a lifetime of shame. The subject would go through a period of cleansing prior to the ceremony. Women were tattooed as well as men, but to a much lesser extent. Happily, some of these traditions have survived to the modern day.

Polynesian tattooing goes back over two thousand years. The artists would use a variety of bone combs and a mallet to imprint the design. The ink was made from the soot of burnt lama nuts. Styles varied from island to island, but all are believed to have significant cultural meaning. Some designs spoke of rank, while others described the attributes of the bearer, with the juxtaposition of symbols giving shades of meaning conceived by the artist. The art itself was usually passed down from a master to a single apprentice (often father to son) because of its spiritual nature. Tattooing was a very painful process with a fair risk of infection lasting ten days (for men), but to halt the process would lead to a lifetime of shame. The subject would go through a period of cleansing prior to the ceremony. Women were tattooed as well as men, but to a much lesser extent. Happily, some of these traditions have survived to the modern day.

In Persia (19th-20thC), it seems the barber could also give you a tattoo while you went in for your weekly bath. The earliest known work in the region is from a Scythian Chief of the 5th Century BCE. The most famous literary mention is found in Rumi, written some 800 years ago. At one time, slaves were tattooed or branded on the face with the initial of their owner. Men often got tattoos on the chest and arms emphasizing strength, while women's were usually on the head or neck to enhance their beauty (though some were temporary). Designs were also employed to cure persistent physical ailments, such as arthritis. Certain tattoos were thought to have magical properties: extending a child's life, keeping away the evil eye, or ensuring a husband's devotion. Tattoos are generally painted on first, then pricked in with a needle, before rubbing in the color. These might be done by gypsy women, the old guy at the gym (for wrestlers), or the local barber. This practice died out among most of the upper classes by 1900, but survived with nomads and villagers.

In Persia (19th-20thC), it seems the barber could also give you a tattoo while you went in for your weekly bath. The earliest known work in the region is from a Scythian Chief of the 5th Century BCE. The most famous literary mention is found in Rumi, written some 800 years ago. At one time, slaves were tattooed or branded on the face with the initial of their owner. Men often got tattoos on the chest and arms emphasizing strength, while women's were usually on the head or neck to enhance their beauty (though some were temporary). Designs were also employed to cure persistent physical ailments, such as arthritis. Certain tattoos were thought to have magical properties: extending a child's life, keeping away the evil eye, or ensuring a husband's devotion. Tattoos are generally painted on first, then pricked in with a needle, before rubbing in the color. These might be done by gypsy women, the old guy at the gym (for wrestlers), or the local barber. This practice died out among most of the upper classes by 1900, but survived with nomads and villagers.

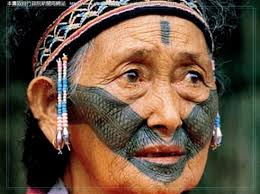

Taiwan has a tradition of facial tattooing amongst the Atayal people dating back 1,400 years. Tatooing is part of the ritual passage into adulthood. Men must prove themselves worthy though their ability to hunt (including headhunting) and women through weaving. This passage was a requirement prior to marriage. The technique is a sacred duty passed down from mother to daughter. It is done with a needle and the charcoal ash of pine trees, with the process taking around ten hours. With the arrival of Christianity, this custom has been all but eradicated with one couple receiving the tattoos in the last hundred years.

Taiwan has a tradition of facial tattooing amongst the Atayal people dating back 1,400 years. Tatooing is part of the ritual passage into adulthood. Men must prove themselves worthy though their ability to hunt (including headhunting) and women through weaving. This passage was a requirement prior to marriage. The technique is a sacred duty passed down from mother to daughter. It is done with a needle and the charcoal ash of pine trees, with the process taking around ten hours. With the arrival of Christianity, this custom has been all but eradicated with one couple receiving the tattoos in the last hundred years.

As you might expect in such an ancient culture, tattoos have gone through several waves of popularity and meaning in Japan. Tattooing is thought to go back some 10,000 years. The women of the indigenous Ainu people of Hokkaido tattooed their lips. They were at times used as symbols of status and spiritualism, while at other times they marked criminals (on the head or forearm) and prostitutes. The modern form developed in the Edo period (1600-1868) alongside the woodblock printing techniques, employing some of its tools. Some believe that elaborate tattoos became popular among the middle classes as a form of rebellion, because they were forbidden to wear the beautiful clothing of the gentry. Today, elaborate Japanese style tattoos are often frowned upon in Japan due to its association with organized crime.

As you might expect in such an ancient culture, tattoos have gone through several waves of popularity and meaning in Japan. Tattooing is thought to go back some 10,000 years. The women of the indigenous Ainu people of Hokkaido tattooed their lips. They were at times used as symbols of status and spiritualism, while at other times they marked criminals (on the head or forearm) and prostitutes. The modern form developed in the Edo period (1600-1868) alongside the woodblock printing techniques, employing some of its tools. Some believe that elaborate tattoos became popular among the middle classes as a form of rebellion, because they were forbidden to wear the beautiful clothing of the gentry. Today, elaborate Japanese style tattoos are often frowned upon in Japan due to its association with organized crime.

Europe has its share of tattooed history as well. Ancient Rome started tattooing all of its new recruits with unit emblems on the left forearm and date of enlistment on the right wrist in the 4th Century BC. Slaves and criminals were also marked with tattoos in that time. Elite warriors of Germanic and Celtic tribes also used elaborate tattoos (and some say branding) of symbols or animals. The Scandinavian Rus Tribe was described by Ahmad ibn Fadlan in the 10th Century as having been, " tattooed from 'fingernails to neck' with dark blue 'tree patterns' and other 'figures.'" Even during the Crusades, warriors would get a tattoo of the Jerusalem cross to be ensured of a Christian burial if they died in combat. While it may not have been widely popular in Europe following the spread of Christianity, tattooing certainly persisted, especially among those who had contact with other cultures.

Europe has its share of tattooed history as well. Ancient Rome started tattooing all of its new recruits with unit emblems on the left forearm and date of enlistment on the right wrist in the 4th Century BC. Slaves and criminals were also marked with tattoos in that time. Elite warriors of Germanic and Celtic tribes also used elaborate tattoos (and some say branding) of symbols or animals. The Scandinavian Rus Tribe was described by Ahmad ibn Fadlan in the 10th Century as having been, " tattooed from 'fingernails to neck' with dark blue 'tree patterns' and other 'figures.'" Even during the Crusades, warriors would get a tattoo of the Jerusalem cross to be ensured of a Christian burial if they died in combat. While it may not have been widely popular in Europe following the spread of Christianity, tattooing certainly persisted, especially among those who had contact with other cultures.

The relationship between people and tattoos has been tumultuous to say the least. Sometimes a beautification, sometimes a test of manhood, sometimes the mark of a criminal, we have been using these permanent markings to differentiate ourselves for a long time. One source cites a 7000 year old tattooed mummy found in Chile. There are far too many cultures who have employed them to explore in a single post, but I hope you have enjoyed this brief exploration. Wander the links below for loads more information.

http://www.apolynesiantattoo.com/polynesian-tattoo-history

http://www.avaikitatauart.com/interview.htm

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/kalkubi

http://www.persian-tattoo.com/history-of-persian-tattoo.html

http://www.vanishingtattoo.com/tattoo_museum/arab_tattoos.html

http://www.culture.tw/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1370&Itemid=157

http://sangbleu.com/2013/12/14/ainus-womens-tattooed-lips/

http://www.iromegane.com/japan/culture/history-of-japanese-tattoo/

http://voices.yahoo.com/tattoos-ancient-europe-historical-look-via-archaeology-2492918.html

http://tattoosymbolism.blogspot.com/2012/03/celtic-knot-tattoo-symbolism.html

http://www.tribal-celtic-tattoo.com/celtic-history2.htm

http://tattoohistorian.com/

Polynesian tattooing goes back over two thousand years. The artists would use a variety of bone combs and a mallet to imprint the design. The ink was made from the soot of burnt lama nuts. Styles varied from island to island, but all are believed to have significant cultural meaning. Some designs spoke of rank, while others described the attributes of the bearer, with the juxtaposition of symbols giving shades of meaning conceived by the artist. The art itself was usually passed down from a master to a single apprentice (often father to son) because of its spiritual nature. Tattooing was a very painful process with a fair risk of infection lasting ten days (for men), but to halt the process would lead to a lifetime of shame. The subject would go through a period of cleansing prior to the ceremony. Women were tattooed as well as men, but to a much lesser extent. Happily, some of these traditions have survived to the modern day.

Polynesian tattooing goes back over two thousand years. The artists would use a variety of bone combs and a mallet to imprint the design. The ink was made from the soot of burnt lama nuts. Styles varied from island to island, but all are believed to have significant cultural meaning. Some designs spoke of rank, while others described the attributes of the bearer, with the juxtaposition of symbols giving shades of meaning conceived by the artist. The art itself was usually passed down from a master to a single apprentice (often father to son) because of its spiritual nature. Tattooing was a very painful process with a fair risk of infection lasting ten days (for men), but to halt the process would lead to a lifetime of shame. The subject would go through a period of cleansing prior to the ceremony. Women were tattooed as well as men, but to a much lesser extent. Happily, some of these traditions have survived to the modern day. As you might expect in such an ancient culture, tattoos have gone through several waves of popularity and meaning in Japan. Tattooing is thought to go back some 10,000 years. The women of the indigenous Ainu people of Hokkaido tattooed their lips. They were at times used as symbols of status and spiritualism, while at other times they marked criminals (on the head or forearm) and prostitutes. The modern form developed in the Edo period (1600-1868) alongside the woodblock printing techniques, employing some of its tools. Some believe that elaborate tattoos became popular among the middle classes as a form of rebellion, because they were forbidden to wear the beautiful clothing of the gentry. Today, elaborate Japanese style tattoos are often frowned upon in Japan due to its association with organized crime.

As you might expect in such an ancient culture, tattoos have gone through several waves of popularity and meaning in Japan. Tattooing is thought to go back some 10,000 years. The women of the indigenous Ainu people of Hokkaido tattooed their lips. They were at times used as symbols of status and spiritualism, while at other times they marked criminals (on the head or forearm) and prostitutes. The modern form developed in the Edo period (1600-1868) alongside the woodblock printing techniques, employing some of its tools. Some believe that elaborate tattoos became popular among the middle classes as a form of rebellion, because they were forbidden to wear the beautiful clothing of the gentry. Today, elaborate Japanese style tattoos are often frowned upon in Japan due to its association with organized crime. Europe has its share of tattooed history as well. Ancient Rome started tattooing all of its new recruits with unit emblems on the left forearm and date of enlistment on the right wrist in the 4th Century BC. Slaves and criminals were also marked with tattoos in that time. Elite warriors of Germanic and Celtic tribes also used elaborate tattoos (and some say branding) of symbols or animals. The Scandinavian Rus Tribe was described by Ahmad ibn Fadlan in the 10th Century as having been, " tattooed from 'fingernails to neck' with dark blue 'tree patterns' and other 'figures.'" Even during the Crusades, warriors would get a tattoo of the Jerusalem cross to be ensured of a Christian burial if they died in combat. While it may not have been widely popular in Europe following the spread of Christianity, tattooing certainly persisted, especially among those who had contact with other cultures.

Europe has its share of tattooed history as well. Ancient Rome started tattooing all of its new recruits with unit emblems on the left forearm and date of enlistment on the right wrist in the 4th Century BC. Slaves and criminals were also marked with tattoos in that time. Elite warriors of Germanic and Celtic tribes also used elaborate tattoos (and some say branding) of symbols or animals. The Scandinavian Rus Tribe was described by Ahmad ibn Fadlan in the 10th Century as having been, " tattooed from 'fingernails to neck' with dark blue 'tree patterns' and other 'figures.'" Even during the Crusades, warriors would get a tattoo of the Jerusalem cross to be ensured of a Christian burial if they died in combat. While it may not have been widely popular in Europe following the spread of Christianity, tattooing certainly persisted, especially among those who had contact with other cultures.The relationship between people and tattoos has been tumultuous to say the least. Sometimes a beautification, sometimes a test of manhood, sometimes the mark of a criminal, we have been using these permanent markings to differentiate ourselves for a long time. One source cites a 7000 year old tattooed mummy found in Chile. There are far too many cultures who have employed them to explore in a single post, but I hope you have enjoyed this brief exploration. Wander the links below for loads more information.

http://www.apolynesiantattoo.com/polynesian-tattoo-history

http://www.avaikitatauart.com/interview.htm

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/kalkubi

http://www.persian-tattoo.com/history-of-persian-tattoo.html

http://www.vanishingtattoo.com/tattoo_museum/arab_tattoos.html

http://www.culture.tw/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1370&Itemid=157

http://sangbleu.com/2013/12/14/ainus-womens-tattooed-lips/

http://www.iromegane.com/japan/culture/history-of-japanese-tattoo/

http://voices.yahoo.com/tattoos-ancient-europe-historical-look-via-archaeology-2492918.html

http://tattoosymbolism.blogspot.com/2012/03/celtic-knot-tattoo-symbolism.html

http://www.tribal-celtic-tattoo.com/celtic-history2.htm

http://tattoohistorian.com/

Thursday, April 3, 2014

Jobs - Barber

Well, there are loads of medical professionals in my family, and if this writing thing doesn't work out, I'm thinking of barber college, so this subject seemed like a natural choice.

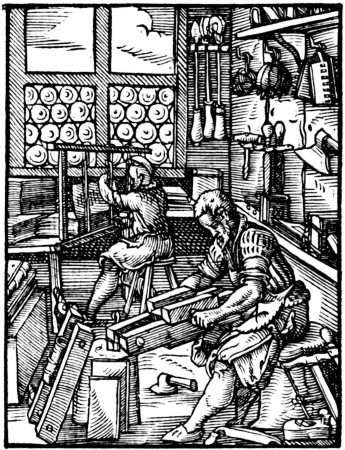

As many of us know, the barber of the medieval period did a heck of a lot more than trim his customer's hair, though that was an important part of his profession (someone had to keep the churchmen appropriately tonsured). The barber saw to the wounded soldier on the battlefield and the village peasant with a toothache. The red and white striped poles (with blue added in the USA), representing blood and bandages, still advertise the historical connection between style and surgery that once existed in the trade.

The barber was a medical catch-all for the common man. Obviously the practice varied from place to place and from professional to professional, but you might visit your barber to: buy medicine, have a tooth pulled, let some blood (yay leeches), get a shave and a haircut, have that nagging hernia fixed, receive an enema, or get a limb removed (often without the benefit of anesthetic). Deaths due to blood loss and/or shock from these surgeries seemed to be relatively common, but I guess if you had a gangrenous leg, death was coming for you anyway, so why not take the chance?

Training for these medical professionals was purely practical. Barbers went through a period of apprenticeship with a master, just like the other trades. The learned doctors often remained at universities serving more as consultants and researchers than practicing medical professionals, leaving the bloody work to the other medical professionals. Surgery was often thought beneath the dignity of the doctor. Remember that the art of balancing of humors was the medical science of the time and prayer was often prescribed. Though some barbers showed great ingenuity in method and invention in their trade, a fair number are thought to have been illiterate.

With all of the fighting going on in the Middle Ages, there was plenty of opportunity for barbers to practice their arts. Being that barbers were taught in a hands-on style, it is probable that they were willing to innovate in ways that theoreticians were not. Advances were also made in natural anesthetics and antiseptics which saved many lives. Of course there was no understanding of how infections originated, so there was always a significant risk of infection with any operation.

Many barbers would travel from town to town offering their services to those in need (or in want. who really needs a leeching?). Being that barbering was a practical art, it seems likely that these practitioners consorted with others of related trades (midwives, herbalists, etc) from time to time, pooling their knowledge for the betterment of all. Some secrecy is to be expected in these businesses, but I can't imagine someone keeping to themselves a better way to remove an arrow from a wound or the right ingredients for a poultice.

Perhaps you wouldn't want to hang out at the barber shop during the Medieval period, but you'd be glad it was there. When prayer and humor balancing were being offered as prescriptions, these men (and probably a few women) were doing the real work. That doesn't mean that everything they did was positive, just often of more use than their better educated peers in the university. A visit to the barber might get your head drilled or a limb removed, but it's still a bit of a crap-shoot today when you're trying to find a new doctor, am I right?

http://www.swide.com/art-culture/history/barber-shop-pole-history/2013/09/29

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barber_surgeon

http://ancientstandard.com/2011/02/18/medieval-barbers-taking-care-of-more-than-just-haircuts/

http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/broughttolife/people/barbersurgeons.aspx

http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/gcsebitesize/history/shp/middleages/medievalsurgeryrev1.shtml

As many of us know, the barber of the medieval period did a heck of a lot more than trim his customer's hair, though that was an important part of his profession (someone had to keep the churchmen appropriately tonsured). The barber saw to the wounded soldier on the battlefield and the village peasant with a toothache. The red and white striped poles (with blue added in the USA), representing blood and bandages, still advertise the historical connection between style and surgery that once existed in the trade.

The barber was a medical catch-all for the common man. Obviously the practice varied from place to place and from professional to professional, but you might visit your barber to: buy medicine, have a tooth pulled, let some blood (yay leeches), get a shave and a haircut, have that nagging hernia fixed, receive an enema, or get a limb removed (often without the benefit of anesthetic). Deaths due to blood loss and/or shock from these surgeries seemed to be relatively common, but I guess if you had a gangrenous leg, death was coming for you anyway, so why not take the chance?

Training for these medical professionals was purely practical. Barbers went through a period of apprenticeship with a master, just like the other trades. The learned doctors often remained at universities serving more as consultants and researchers than practicing medical professionals, leaving the bloody work to the other medical professionals. Surgery was often thought beneath the dignity of the doctor. Remember that the art of balancing of humors was the medical science of the time and prayer was often prescribed. Though some barbers showed great ingenuity in method and invention in their trade, a fair number are thought to have been illiterate.

With all of the fighting going on in the Middle Ages, there was plenty of opportunity for barbers to practice their arts. Being that barbers were taught in a hands-on style, it is probable that they were willing to innovate in ways that theoreticians were not. Advances were also made in natural anesthetics and antiseptics which saved many lives. Of course there was no understanding of how infections originated, so there was always a significant risk of infection with any operation.

Many barbers would travel from town to town offering their services to those in need (or in want. who really needs a leeching?). Being that barbering was a practical art, it seems likely that these practitioners consorted with others of related trades (midwives, herbalists, etc) from time to time, pooling their knowledge for the betterment of all. Some secrecy is to be expected in these businesses, but I can't imagine someone keeping to themselves a better way to remove an arrow from a wound or the right ingredients for a poultice.

Perhaps you wouldn't want to hang out at the barber shop during the Medieval period, but you'd be glad it was there. When prayer and humor balancing were being offered as prescriptions, these men (and probably a few women) were doing the real work. That doesn't mean that everything they did was positive, just often of more use than their better educated peers in the university. A visit to the barber might get your head drilled or a limb removed, but it's still a bit of a crap-shoot today when you're trying to find a new doctor, am I right?

http://www.swide.com/art-culture/history/barber-shop-pole-history/2013/09/29

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barber_surgeon

http://ancientstandard.com/2011/02/18/medieval-barbers-taking-care-of-more-than-just-haircuts/

http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/broughttolife/people/barbersurgeons.aspx

http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/gcsebitesize/history/shp/middleages/medievalsurgeryrev1.shtml

Tuesday, April 1, 2014

What is Feudalism?

|

| http://www.arteguias.com/biografia/carlomagno.htm |

Yeah yeah, I can hear the whiners, "anybody who is reading a blog about researching Medieval history knows what feudalism is." Well, that may be so, but I have no idea who all reads this thing, so from time to time I'm going back to basics. As it is, this post only scrapes the surface of a rather complex topic. As always, if you want more, go to the pages listed at the end.

Feudalism is a term that has been bandied about to describe the political system of the Medieval period for some time (Wikipedia suggests the 18th C with the term feudal system from the early 17th C). Unlike Fascism or Communism, Feudalism never had a cohesive ideology. Consequently, there is no "model" feudal society to be found in history or literature. It was simply a term assigned to encapsulate the most common political elements seeing use at the time. In essence, I'm going to ignore my own basic question and explore the political realities of the period instead of a label attached hundreds of years later.

Medieval political systems were born in the wake of the collapsing Roman Empire. As trade died, Europe reverted to an almost completely agrarian economy. This decentralization of power left significant opportunity for groups of warriors to take up arms and fill the power vacuum. Petty kingdoms rose to offer "protection" to the nearby farmers. In return for this protection, the kings were granted tithes and goods. From this position , these kings came to act as lawgivers and serve judicial positions.

The basic contract described under the Feudal heading is that between Lord (or later the knight) and peasant or serf (a.k.a. villein). In this relationship, the landholder gives the farmer protection and a parcel of land to work. In return, the farmer owes a share in the proceeds (or a certain set value), work on the landholder's property and possibly service in the military. Over time, this relationship developed wildly different rules across Europe. Serfs were not allowed to leave their farms without the permission of the landholder and in many situations had no rights at all. Peasants had a limited amount of personal freedom, working like the serfs as sharecroppers, or at trades in the villages. The later return of cities, following the reopening of trade, had a significant impact on this relationship.

As kings increased in power, they accumulated land through conquest and attracted followers. To reward these followers for good service, kings would grant control over a portion of their holdings (a fief) in return for oaths of fealty and service. The oaths of service could include military support (or equal financial compensation), attendance at court, and the providing of council. In return for these oaths, the king swore to give military protection to their vassals. It's unclear exactly when these granted titles became hereditary, but this seems to be where the trouble started, as personal relationships between lord and vassal became traditional bonds between families.

Depending upon the king's holdings, these bestowed fiefs could range in size considerably. Many times, the larger fiefs were further divided. These smaller landholders would then owe fealty to the Lord as well as the king (his liege lord). These divided loyalties provided for plenty of intrigue over the years. Additionally, as communication began to return to Europe, and established aristocracies began to intermarry for political and financial purposes, control of disparate fiefs, owing loyalty to different liege lords became much more common. It was also quite possible that some of the sworn lords had greater holdings than their kings. You can guess how binding the oaths of fealty worked out then.

Not to be ignored, the Church was also tied into the political systems of the time. Churches and monasteries were frequently granted title to tracts of land in the wills of aristocrat's, in return for spiritual considerations. Younger sons, who would not generally inherit land, often joined the church to achieve positions of power. Since no churchman could hold title (unless you want to count the Pope), all lands were owned by the Church as a whole, though administered locally. In fact, the Catholic Church became the largest landholder in Europe. Add to this the fact that the Church was tax exempt, all worshipers paid a 10% income tithe (on pain of hellfire), and that all peasants and serfs worked on Church land for free. Because of the structure of the Church, it benefited significantly from the hereditary nature of land.

The Medieval period was not a planned organization, but a slowly developing series of contracts paid for in blood and nurtured with toil. There was no fundamental ideology driving it. It was founded on the patronage of warrior brotherhoods which grew beyond their provincial influence. As they grew, the beautiful simplicity of personal relationships reinforced by oaths of faith and service became a complex web of obligations. When these traditions calcified, establishing what we commonly think of today as Feudalism, it would not have been recognizable to those warrior chiefs who offered protection to their neighbors.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feudalism

http://www.usna.edu/Users/history/abels/hh315/Feudal.htm

http://faculty.history.wisc.edu/sommerville/123/feudalism.htm

http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/medieval_church.htm

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)