|

| http://blogs.unimelb.edu.au/librarycollections/files/2014/01/Forest_14992.jpg |

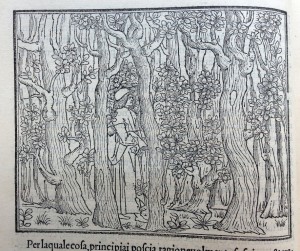

In all honesty though, the Middle Ages were the time when humanity began to tame the forest. Forest use was highly regulated regarding the felling of timber and the pasturing of animals (no goats or sheep, thank you very much). Deer may have been protected, but there are plenty of other animals to hunt. Ferns and undergrowth were used to stuff the mattresses. Proper husbandry of the forest was essential to much of Medieval village life.

Wood is, obviously, one of the most widely used resource in the forest. Hard woods were employed for erecting defenses (especially before they started employing stone, or later as a quick and cheap substitute), framing homes, building furniture, tools, staves, and so on. Soft woods, branches and undergrowth (not good logs) were primarily used for burning or building fences. Bark could go to the dyer, or into teas and medicines. Charcoal was made, but reserved for the forge, or for use in cities (reducing the chance of fires). Yup, used for pretty much everything. However, they were very strict about what wood could be cut down, and replacing the materials that they used. Burned materials were primarily deadfalls and there were harsh punishments for those who violated the rules of the forest.

Fossier mentions that the peasant of the Middle Ages isn't known for "market gardening." This means that, like their ancestors of the previous few thousand years, foraged to supplement their farming. The list is quite extensive: berries, hazelnuts, almonds, walnuts, olives, mushrooms, chestnuts, medlars, acorns, squash, pumpkins, tubers, cherries, figs, apples, quinces, pears, garlic, onions, mint, oregano, and so on. To this list, he adds items that could be planted, such as asparagus, leeks, chard, cabbage, rhubarb, artichokes, carrots, parsnip, and beets (I assume this "planting" is much like it is thought our ancient ancestors may have planted seeds in specific places so they might have a good idea where to look for food when they returned the following year). Because foraging was such an important part of peasant life, during wartime, they could live off the land for quite some time.

With all of this activity going on, a walk in the forest anywhere near a settlement, would hardly be a solitary experience. It makes me think of all the old Czech women coming home on the trams, with their baskets full of freshly picked mushrooms (though the best spots are still a carefully guarded secrets). Add in foresters cutting down trees, people collecting fuel for the fires, with forest guards keeping a careful eye on them all, and you have quite a busy place. Certainly, those who lived there year-round (making charcoal, hiding out from the law, or some other reason) garnered a certain reputation for consorting with demons, but the forest was not as forbidding a place as we might imagine.

No comments:

Post a Comment